One of the most notable instances in which the marketplace demonstrated a firm control of the creative freedom of mass media occurred in the music industry at the end of the 20th century with the reemergence of boy bands. The concept of a boy band was nothing new, as it had roots dating back as early as the 1960’s, when the Monkees and the Beatles ruled the industry. With each successive decade came a new, refurbished version of the boy band-the 1970’s had Menudo, the 1980’s had New Kids on the Block and New Edition, and the 1990’s had the Backstreet Boys, N*Sync, and 98 Degrees, amongst many others. These bands incited a craze that not only dominated the airwaves, but filled the newsstands and adorned the bedroom walls of millions of teeny boppers around the world. Although each respective band of the late 90’s had its own distinct name and projected image, all were derived from what was more or less the same general formula. The groups typically featured several young male singers in their mid to late teens or early twenties who, in addition to singing, danced to highly choreographed numbers. Ironically musical instruments were rarely played by members, thus making them more of a vocal group than a band. Backstreet Boys, O*Town and other bands of this era were not spontaneously created, but were methodically contrived by talent managers and producers-such as the notorious Lou Pearlman of Trans Atlantic Records- who, upon realizing the potential to capitalize on a new generation of consumers, selected group members based on appearance, singing ability, and dancing skills. These boy bands were also classically characterized by changing their appearances to adapt to new fashion fads (they often donned flashy matching ensembles), following mainstream music trends, performing complex dances, and producing elaborate shows.

As important as the selection of the members of a boy band was, this alone did not determine the commercial success of the group. Record companies, aware of the desire for the consumer to “connect” with the group, capitalized on this by highlighting a distinguishing characteristic of each member and portraying him as having a certain image. By branding members with particular personality stereotypes such as “the shy one” or “the rebel” individuals were able to identify with a member or multiple members of a group on a more personal level and record companies were able to strategically reel consumers. A perfect example of this occurred with the group N*Sync. With blond curly hair, piercing blue eyes, and a sweet high pitched voice, Justin Timberlake the youngest of the group, was branded as “the baby” of the group. Timberlake subsequently attracted a large fan base of very young girls that identified with this stereotyped image whether it be because Timberlake was the closest to their own age or simply because they bought into his projected sweet persona. Chris Kirkpatrick, another member of N*Sync, was Timberlake’s image foil; 10 years his senior, Kirkpatrick sported facial hair, unusual dreadlocked hairdo, and large hoop earrings, Kirkpatrick was often dubbed as “the crazy one” and thus, attracted a slightly older fan base of girls who could identify with this particular persona.

were able to identify with a member or multiple members of a group on a more personal level and record companies were able to strategically reel consumers. A perfect example of this occurred with the group N*Sync. With blond curly hair, piercing blue eyes, and a sweet high pitched voice, Justin Timberlake the youngest of the group, was branded as “the baby” of the group. Timberlake subsequently attracted a large fan base of very young girls that identified with this stereotyped image whether it be because Timberlake was the closest to their own age or simply because they bought into his projected sweet persona. Chris Kirkpatrick, another member of N*Sync, was Timberlake’s image foil; 10 years his senior, Kirkpatrick sported facial hair, unusual dreadlocked hairdo, and large hoop earrings, Kirkpatrick was often dubbed as “the crazy one” and thus, attracted a slightly older fan base of girls who could identify with this particular persona.

The heavy reliance of record companies upon the aforementioned stereotypes left little, if any, creative freedom to groups and rendered members essentially unable to venture outside of the box created for them. The key factor of boy bands was to remain trendy and therefore the band was expected to conform not only to the most recent fashion, but musical, trends in the popular music scene. Because the majority of the music produced was written and produced by producers who worked with the bands at all times, they were the ones who not only projected the next smash hit, but controlled the group’s sound in a manner in which this would be possible. As the marketing and packaging of boy bands and their image began taking precedent over the quality of music which they were producing, the options which artists and consumers alike were offered became narrower and narrower. Rather than take the chance of venturing into the uncharted waters of the music by trying something new, producers and record labels became content selling the same sort of tunes to the same audience, as that is what was generating maximum profit. In doing so, a vicious cycle was created. Once mass media businesses recognized what types of songs were selling, boy bands were limited to singing and performing the same feigned emotional ballads and pop dance tunes to slightly altered beats, further limiting the musical options available to the public.

Although boy bands were able to make an easy transition into the early 21st century, the commercial success of the “pop” boy bands did not last long. The fan base for these groups grew up, their musical tastes evolved, and a new generation of consumers was established. As this evolution occurred, boy bands did not simply disappear, but once more reemerged with an all new image and sound. Gone were the days of gel tipped hair and cheesy color coded outfits, and in were the days of vintage duds, faux hawks, and eyeliner. The industry waved goodbye to LFO, O-Town, and LMNT, and readily embraced groups such as My Chemical Romance, Sum 41, and Good Charlotte, perpetuating the same old industry song of capitalization, but with a different punkier image and edgier tune.

Although boy bands were able to make an easy transition into the early 21st century, the commercial success of the “pop” boy bands did not last long. The fan base for these groups grew up, their musical tastes evolved, and a new generation of consumers was established. As this evolution occurred, boy bands did not simply disappear, but once more reemerged with an all new image and sound. Gone were the days of gel tipped hair and cheesy color coded outfits, and in were the days of vintage duds, faux hawks, and eyeliner. The industry waved goodbye to LFO, O-Town, and LMNT, and readily embraced groups such as My Chemical Romance, Sum 41, and Good Charlotte, perpetuating the same old industry song of capitalization, but with a different punkier image and edgier tune.

With this rebirth of punk in the boy band scene came the commercialization of yet another movement-indie. Up until a decade ago indie (short for independent) traditionally referred to any form of art-music, film, or literature-that was created without corporate financing and without mainstream influence. In the music industry, “indie” specifically referred to any music that had been produced and funded by any band or label that was not affiliated with major corporate labels such as Sony or Epic. Free from corporate control, indie artists and groups were not under the same profit-based shareholder pressure most record corporations placed on their artists to drive sales, and were consequently freer to release music that did not necessarily have the greatest commercial appeal.

Indie’s independence from corporate control did not last long, as companies began to catch on to the great commercial potential of this genre. Some have accredited the adoption of indie by corporations to the wide success of garage bands such as Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and

Once corporations began to show interest in the indie scene, many smaller music labels similarly grew eager for wider financial success, and began adopting “business practices of major labels once considered anathema in the scene” such as licensing songs to advertising companies and hiring PR firms and street teams to market their records. As this selling out occurred, the definition of indie as a culture in which the truly independent passion for music can be expressed has dissolved and became no more than a money driven branding tool aimed at marketing a particular image. Major labels have continued to use the indie name to continue to attract, and profit off of, a “different” demographic looking for a “different” type of music when in all actuality, indie music mainstream. The true essence of the genre has been lost, and all the consumer is receiving is more unoriginal music, once more exemplifying the narrowing of creative listening options available to the consumer.

The deterioration creativity and creative freedom in mass media due to commercialization is not exclusive to music, as it has had an equally heavy impact on the television and film industries. As the era of pop boy bands came to a close in music, a reality television revolution had begun to emerge. Reality TV, a “genre of television programming which presents purportedly unscripted dramatic or humorous situations, documents actual events, and features ordinary people instead of professional actors”, varies greatly as it encompasses a plethora of subgenres. The most popular subgenres have included Celebreality in which a celebrity is documented going about his or her daily life (The Osbournes, Newlyweds, The Simple Life), talent search shows in which the “next big thing” is to be discovered (American Idol, Pop Stars, America’s Got Talent), self-improvement shows (Extreme Makeover, Queer Eye For the Straight Guy), and job search shows in which pre-screened competitors perform a variety of tasks based on a common skill are judged by a panel of experts as a process of elimination narrows the playing field until a winner is declared (Project Runway, The Apprentice, The Shot).

Once the success of the first modern day reality television shows was observed by mass media businesses, networks wasted no time in rearranging their show lineups to make room for shows of their own, as each network was eager to cash in on a piece of the reality pie. As sitcoms and conventional drama series were pushed aside as more and more reality shows into development the quality and the variety of the programs which the general public was offered began to decline. Viewers were once more caught in a Catch-22 of sorts; they kept tuning in to reality programs because that was all that was offered by networks, and networks kept offering them because that is what drew ratings and revenue. And so the cycle continues.

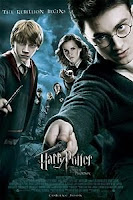

The plaguing of music and television by mass media business strategy has also begun to plague the film industry, albeit at a slower pace. The cinema classics of the past greatly differ from modern day feature films, as the pursuit of profit has gradually taken precedent over quality and construction. Actors, producers, and critics such as Oscar Winning Sir Michael Caine have attributed the deterioration of films to the general “lacking in dialogue, character, and plot”. Over the years  like the music and television industries, has become a product of corporate interests aimed at generating the maximum amount of money possible, and has thus fallen subject to the same formulaic methods of production that were previously noted in the music industry. As the emphasis of production has shifted away from cohesiveness and fluidity, special effects, action, violence, and sex have become the determining factors in the success of a picture. Obvious patterns in the movies have emerged as studios note one film’s success and continue to emulate it in a slew of succeeding movies. Some notable patterns include the “teen queen” movies of the late 90’s (She’s All That, 10 Things I Hate About You, Clueless, Never Been Kissed, American Pie, Can’t Hardly Wait), superhero movies (X-Men Series, Spiderman Series, The Punisher, Hulk),“spoof movies” (Scary Movie Series, Date Movie, Epic Movie) and fantasy movies (Harry Potter Series, The Lord of the Rings Series, Chronicles of Narnia Series, Eragon, The Golden Compass, Pan’s Labyrinth). With the scrapping of the responsibility “to give audiences something better” the film industry has grown content churning out the same sorts of hits with the same basic plot lines to gain profit. In doing so, creativity is once more stifled, and the options of films which consumers are offered are significantly lessened.

like the music and television industries, has become a product of corporate interests aimed at generating the maximum amount of money possible, and has thus fallen subject to the same formulaic methods of production that were previously noted in the music industry. As the emphasis of production has shifted away from cohesiveness and fluidity, special effects, action, violence, and sex have become the determining factors in the success of a picture. Obvious patterns in the movies have emerged as studios note one film’s success and continue to emulate it in a slew of succeeding movies. Some notable patterns include the “teen queen” movies of the late 90’s (She’s All That, 10 Things I Hate About You, Clueless, Never Been Kissed, American Pie, Can’t Hardly Wait), superhero movies (X-Men Series, Spiderman Series, The Punisher, Hulk),“spoof movies” (Scary Movie Series, Date Movie, Epic Movie) and fantasy movies (Harry Potter Series, The Lord of the Rings Series, Chronicles of Narnia Series, Eragon, The Golden Compass, Pan’s Labyrinth). With the scrapping of the responsibility “to give audiences something better” the film industry has grown content churning out the same sorts of hits with the same basic plot lines to gain profit. In doing so, creativity is once more stifled, and the options of films which consumers are offered are significantly lessened.

Alberge, Dalya. "Caine hits out against today's 'banal' films." The Times Online. Sept. 2006.

Andrews, Catherine. "If it's cool, creative and different, it's indie." CNN.com.Oct., 2006.

"Boy band." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 11 Feb 2008, 02:22 UTC. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 11 Feb 2008 <http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Boy_band&oldid=190525878>.

"Independent music." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 10 Feb 2008, 13:17 UTC. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 11 Feb 2008 <http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Independent_music&oldid=190380470>.

Kaufman, Gil. "The New Boy Bands."MTV.com. Date Unknown.

Lamb, Bill. "Top 10 Boy Bands."About.com. Date Unknown.

Olsen, Eric. "Once again, boy bands say 'bye, bye, bye'." MSNBC. March, 2004.

"Reality television." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 5 Feb 2008, 16:46 UTC. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 11 Feb 2008 <http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Reality_television&oldid=189285855>.

Rowen, Beth. "History of Reality TV." Infoplease.com. July, 2001.

No comments:

Post a Comment